Cosima Gillhammer is a Junior Research Fellow in English at Christ Church, Oxford. Her primary research interests focus on textual criticism, medieval English Bible translation, biblical scholarship, and the liturgy in the context of the Wycliffite Bible. The post below is an edited version of Cosima’s presentation at the Teaching the Codex workshop on Hybridity on 17th May 2024.

Where to start?

When teaching with manuscripts, one is always faced with the pragmatic question of which manuscripts to select for a particular class or course. It can be difficult to choose: which manuscript incorporates an appropriate range of features to support a particular pedagogical goal? Here I would like to introduce a lesser-known manuscript from the Bodleian Library which I have found particularly useful in encouraging students to think about aspects of hybridity in the medieval book – instances where manuscripts incorporate mixed materials, texts, or languages.

Oxford, Trinity College, MS 29 contains a universal history of the world in Middle English and Latin, starting with Adam and Eve and ending incomplete at the time of Hannibal. It was compiled from a range of different sources, both English and Latin, by a single compiler-scribe in the late fifteenth century. Its most likely context was the use in an Augustinian house in the South of England. An unusual and impressive text surviving in a single manuscript, it is particularly interesting in view of hybridity of a textual, material, linguistic, and generic kind. [1]

Textual hybridity:

The text is compiled from both manuscript and print sources. A large part of the text is copied from Caxton’s printed edition of John Trevisa’s translation of Ranulph Higden’s Polychronicon (1482). The compiler meticulously excerpted sections from Caxton’s print, copied them out by hand, and incorporated them into the universal history alongside manuscript sources. No distinction is made visually or textually in how these different sources are used: both manuscript and print sources are rewritten and incorporated into a larger whole – a universal history of the world with its own sustained purpose and perspective. As such, this manuscript can serve as a useful example to demonstrate to students how the transition from manuscript to print was not a unidirectional process, challenging common assumptions with which students often come to the classroom.

Material hybridity:

The manuscript is written on paper but on f. 211r it incorporates an illustration on parchment, likely culled from another manuscript and glued onto the page. This schematic map of Jerusalem tends to be popular with students, who often eagerly try to work out how to read it. It also encourages them to think about how materials were used, and reused, in medieval textual culture.

Linguistic hybridity:

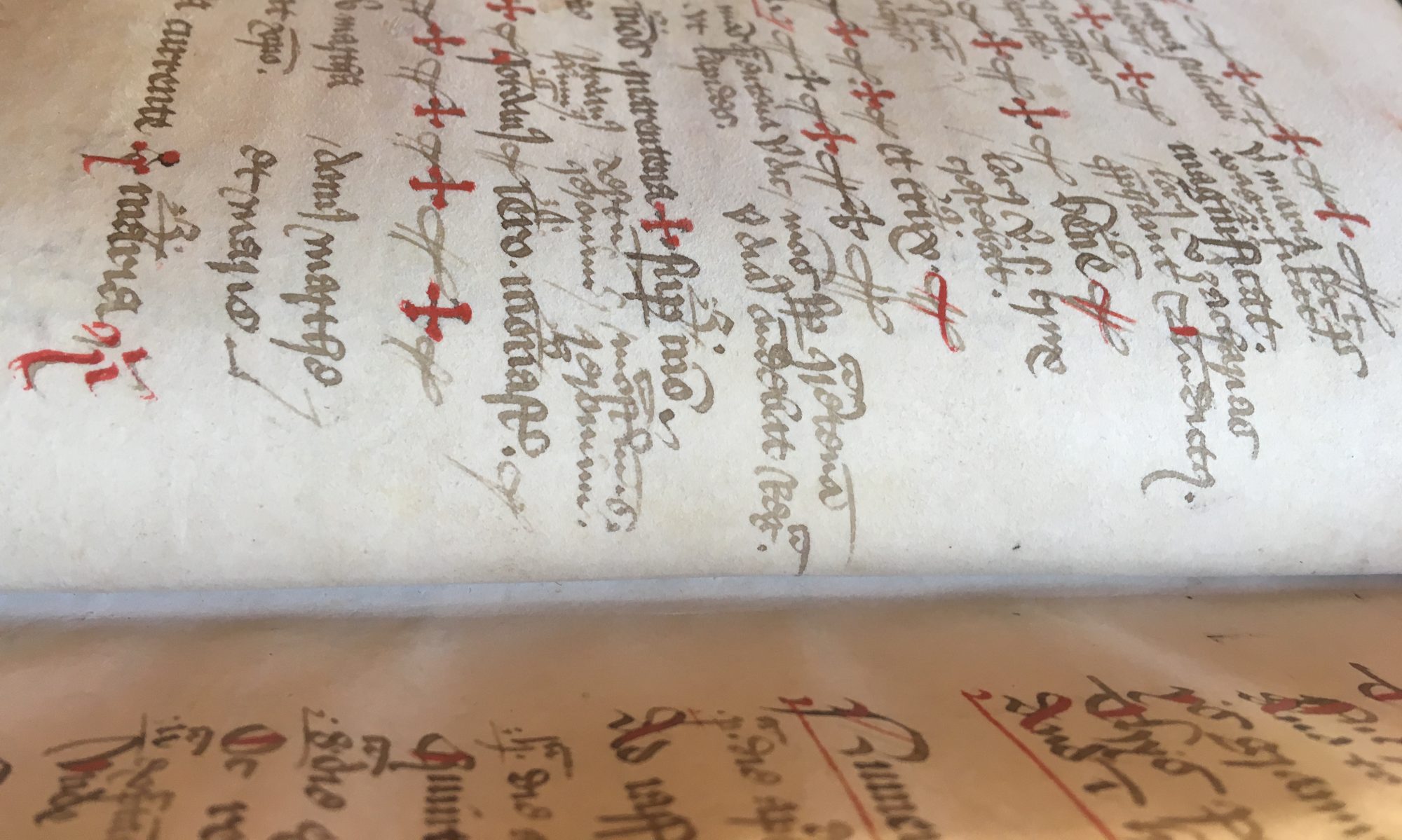

Although the text is predominantly written in Middle English, it also incorporates some sections in Latin. The compiler-scribe observes the hierarchy of scripts, presenting Latin sections in a larger display script. The image below shows a section of the Holy Cross Legend included in the text in both Latin and Middle English, providing ample material for discussion in the classroom about how the prestige attached to Latin is visually represented on the page.

Hybridity of genre and form:

The manuscript incorporates a number of recycled pages containing an excerpt from Gower’s Confessio Amantis (ff. 189r-194v). Originally written in a different context, these recycled pages are particularly striking as they contain verse, setting them visually apart from the prose narrative in the preceding text. Nonetheless, the verse excerpt forms an integral part of the text as a whole, and is incorporated at an appropriate point into the main narrative.

A hybrid in every way:

This manuscript, then, has a bit of everything when it comes to hybridity. Such multiform hybridity is not at all unusual in late medieval manuscripts, and in fact is part and parcel of many medieval miscellanies. However, this manuscript is not a miscellany in the traditional sense as the excerpts from different kinds of sources are incorporated into a new framework and larger whole, forming a sustained narrative. In this sense, this manuscript is an interesting example of how aspects of hybridity in medieval manuscripts relate to ideas of completeness, wholeness, and consistency. This makes it a very useful object with which to challenge students to think outside of the categories with which they are often presented in courses on the medieval period, such as medieval vs Early Modern, manuscript vs print, parchment vs paper, or verse vs prose.

I use this manuscript regularly in classes at the Bodleian Library to encourage students to question such dichotomies. After a session at the library which is focused on letting the students work with the physical object, I come back to this manuscript in tutorials to think more broadly about how medieval codicological practices give rise to such dichotomies but also transcend them. What do we do with cases which don’t fit such a dichotomy? One way of thinking about this which tends to appeal to students in particular is to compare textual hybridity with both printed and manuscript sources to the digital age, thinking about similarly hybrid ways in which we use printed and digital texts, and asking whether there are any differences to medieval practices.

Beyond this, I also use this manuscript to think with the students about the ways in which hybridity is used here in the service of a new, greater textual whole. The result of the process of compilation is a new text with its own intentionality, logic, and distinct audience. Does this manuscript, perhaps, become something different from its source texts precisely because of its hybrid nature?

I conclude my teaching with this manuscript with more practical considerations. For students it is often difficult to identify such codicological and textual aspects of the kind highlighted above when working with a modern edition of the text rather than the physical manuscript. I therefore invite them to explore how the modern edition of this manuscript variously brings to the fore, or obscures, such hybrid features in this particular text – in practical terms, where can we find such information in the edition, and what can we do with it in analytical terms? This exercise will be applicable more broadly to other texts and editions, and in this way teaching with the manuscript can help students feel more confident in their future work on the material text.

[1] For further details on the manuscript see my edition, A Late-Medieval History of the Ancient and Biblical World, 2 vols (Winter 2021-22)

Great!

LikeLike

Great example of how hybrid texts make teaching more engaging and meaningful for students.

Lanquill

LikeLike