Dr Sian Witherden is a rare books and manuscripts specialist who has worked in both special collections libraries and the antiquarian book trade. This final post in a series on collation explains how to handle more complex examples, and highlights some useful resources.

Going further

In part 3, we covered how to collate the Bodleian’s second edition of Cordyal (c.1494), and how to write an associated collation formula. However, not all books have such a straightforward physical structure. Building on the foundations of what you have learned already, part 4 will engage with some more complicated examples. At the end, I also offer some suggestions for further reading on the topic.

Accommodating long books

As explored in the previous post, gatherings in early printed books were often signed according to the 23-letter Latin alphabet. But how did this work for books with more than 23 gatherings?

The most common strategy was to restart the alphabetical sequence but with some kind of distinction. For example, if the first 23 gatherings were signed with lowercase letters, then uppercase letters might follow. Alternatively, the second alphabetical sequence might use doubled letters, i.e. ‘aa’, ‘bb’, ‘cc’, etc. or ‘AA’, ‘BB’, ‘CC’ etc. For exceptionally long editions, tripled and even quadrupled letters can be found. In collation formulae, signatures made up of a duplicated letters will often be indicated with the relevant number before the letter, e.g. 2a for gathering ‘aa’, 3a for ‘aaa’, etc. (In Bod-Inc, the number at the front is given in superscript, i.e. 3a would refer to gathering ‘aaa’).

Let’s have a closer look at a book with more than 23 gatherings: Bodleian Library Auct. 2Q 2.29 (digitized in full here). This is Antoine Vérard’s edition of De la bataille judaique (a French translation of Flavius Josephus’s De bello Judaico), printed after December 1492.[1] You can read more about the edition, especially its interesting woodcut illustrations, in this British Library blog post on Vérard. The book was printed in folio format, i.e. each sheet of paper was folded just once. The lengthy book spans 264 folios (i.e. 528 pages), amounting to 34 gatherings.

The first gathering is, unsurprisingly, signed ‘a’. Note, though, that the first two rectos in are unsigned (i.e. the first printed signature appears on sig. a3r). It is relatively common to find that the very first folio of an early printed book has no printed signature. Pages with elaborate printed borders, like sig. a2r here, are another place where signatures are often omitted.

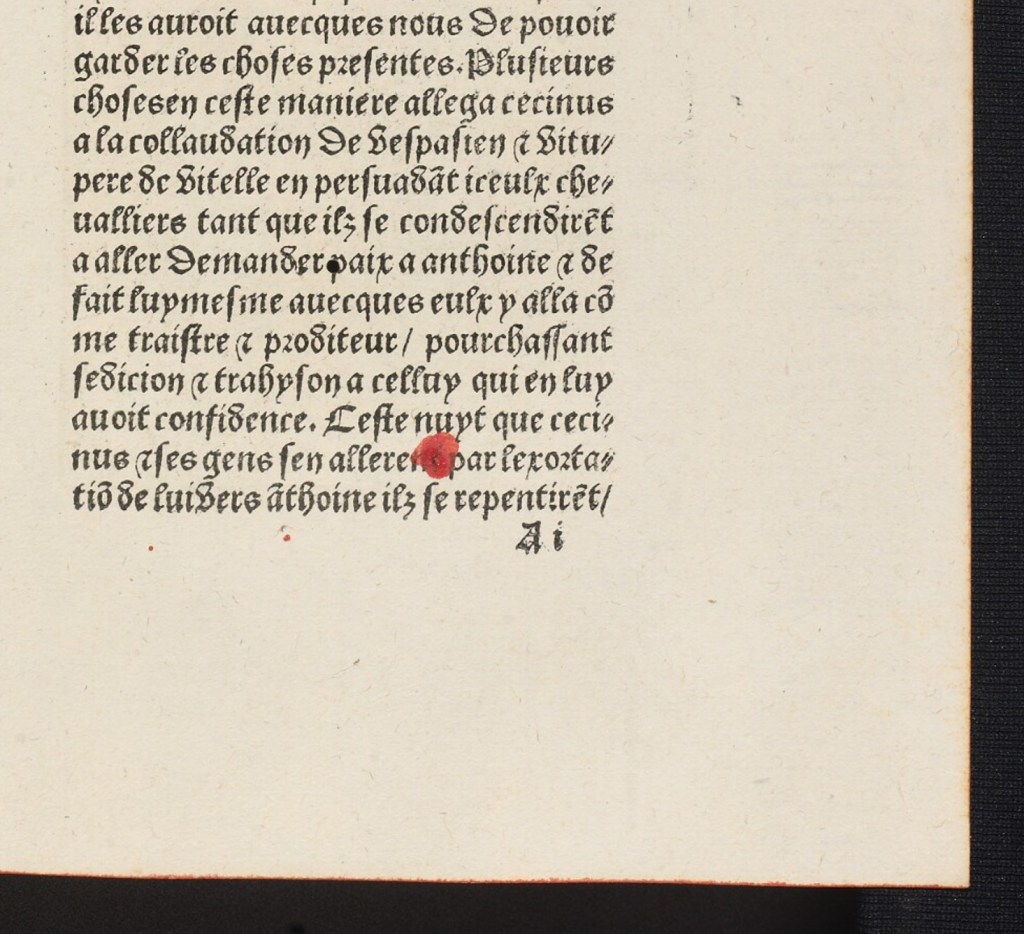

After gathering ‘a’, the next 22 gatherings continue to follow the Latin alphabet from ‘b’ through to ‘z’. Then, at the 24th gathering, the alphabetical sequence starts a second time – except this time with upper case letters. Below you can see the lower-right hand corner of the first leaf of the 24th gathering, i.e. sig. A1r. For context, the red mark here must have been introduced accidentally during the rubrication phase (see my previous blog post on decorative features).

Reproduced from Digital Bodleian under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

The remaining 10 gatherings cover the letters B-L. The ideal copy of this edition should therefore have the following collation: a-e8 f6 g-z A-I8 K6 L4 (note especially that all gatherings between g and I are the same length, which can concisely be summarized as g-z A-I8). The Bodleian copy, however, does not look quite like this.

Describing incomplete copies

If you turn to the end of De la bataille judaique on Digital Bodleian, you will see a stub between L3v and the recto of first lower flyleaf:

Reproduced from Digital Bodleian under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

This missing leaf, sig. L4, would have been blank on both sides. We can establish this, for example, by looking at the description of the copy in the British Library in which the blank final leaf is present.[2]

How do we describe this loss? A relatively common practice is to give the collation of the ideal copy in full, and then to indicate what is missing, i.e. ‘Wanting the blank leaf L4’. This is more or less what you will find in the Bod-Inc entry for this copy under J-225, albeit with the number 4 in subscript, i.e. L4. Bod-Inc also informs us that sig. a1 is backed (i.e. mounted on another piece of paper), which you can see in the digitization through a hole on the recto:

Reproduced from Digital Bodleian under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Books without signatures

You will find that some early printed books — especially earlier incunables — have no printed signatures at all. One example of this is the edition of Gratian’s Decretum printed by Heinrich Eggestein in Strassburg in 1471.[3] For context, the Decretum was a fundamentally important collection of canon law (i.e. ecclesiastical law). You can see the first printed page of the Bodleian’s visually impressive copy below, and the full digitization here (Bodleian Library Auct. 4Q 1.7).

![A photograph of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. 4Q 1.7, sig. [a1], which has no printed signature in the lower right-hand corner. The page is elaborately decorated with an illustration, a decorative initial ‘H’, and rubrication in red and blue.](https://teachingthecodex.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/fig.-29-bodleian-library-auct-4q-1-7_00007_fol-a1-r_reduced-1.jpg?w=756)

Reproduced from Digital Bodleian under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

In cases like this, the cataloguer assigns signatures but places them in square brackets to indicate the intervention. Our first folio, then, becomes sig. [a1]. Extrapolating this across the entire book, we get a collation of: [a–i10 k l8 m–z A–H10 I K8 L–Z10 2a8]. As this entire book lacks printed signatures, we can simply place a square bracket at the very beginning and end of the formula; in other words, there is no need to write out [a]-[i]10 etc.

Closing Thoughts

At its heart, understanding collation allows for a more nuanced understanding of how early printed books were produced and assembled. A solid grasp of collation also has some obvious practical advantages. If multiple copies of an early printed book are available to you for study, their respective collations may help you to prioritize one. For example, a complete copy might be more beneficial for your research project than a fragmentary one.

This blog post series has presented a model for self-learning, one that potentially takes advantage of the increasing amounts of incunables available online (over 500 incunables are fully digitized on Digital Bodleian alone!). Naturally, digitizations can never fully replace the experience of collating a book manually—especially when it comes to features that are more challenging to image, such as chainlines, watermarks, and stitching. Wherever possible, collating with the book in hand is always preferable. Nevertheless, digital copies are an excellent way to get started on the topic, particularly if you do not have access to a special collections library.

Over the course of this series, we have progressed from a relatively straightforward collation to some more difficult examples, in the process covering all three of the formulae I introduced at the very beginning. However, this has not been an exhaustive survey of the topic, and yet more complex cases certainly exist. Readers seeking to delve deeper may find it helpful to first read Werner (2019) and then move on to resources like Bowers (repr. 1994), Gaskell (1995), and/or Tanselle (2020). Full references can be found in the appendix.

These notes use some common abbreviations explained in Part 1.

[1] See especially Bod-Inc J-225 (describing this copy). For the edition more generally, see BMC VIII 78, GW M15198, and ISTC ij00489000.

[2] BMC VIII 78 (‘the last leaf blank’).

[3] See especially Bod-Inc G-178 (describing this copy). For the edition more generally, see BMC I 67, GW 11351, and ISTC ig00360000.

One Reply to “”