Dr Sian Witherden is a rare books and manuscripts specialist who has worked in both special collections libraries and the antiquarian book trade. This post — the third in a four-part series on collation — offers a ‘guided tour’ of the Bodleian’s second edition of Earl River’s ‘Cordyal’ (1494).

Moving forward

In part 2, we covered the basics of format and established that the second edition of Earl Rivers’ Cordyal (c.1494) is a quarto. With this context in mind, we are in a good position to start the practical process of collation. By the end of part 3, you will understand how this book was put together and know how to write a basic collation formula. I will include relevant images at every stage, but you may also find it helpful to have another tab open in parallel with the full digitization.

Opening the book

When you first (digitally) open the book, you will not immediately reach the printed material. The first three images after the upper cover are of the endpapers. Endpapers are not part of the textblock, but were added by the binder at the front and back of the book for structural support. The endpaper adhered to the inside of the upper cover is known as the ‘upper pastedown’. It is highlighted in blue in the screenshot of the Digital Bodleian navigation pane below. The next endpaper is not adhered, and it is commonly described as the ‘upper flyleaf’ or ‘front free endpaper’. The two sides of the upper flyleaf are highlighted in red below. At the rear of the book, you will find equivalents in the form of the lower pastedown and lower flyleaf. Importantly, endpapers are not counted in the collation.

First Steps

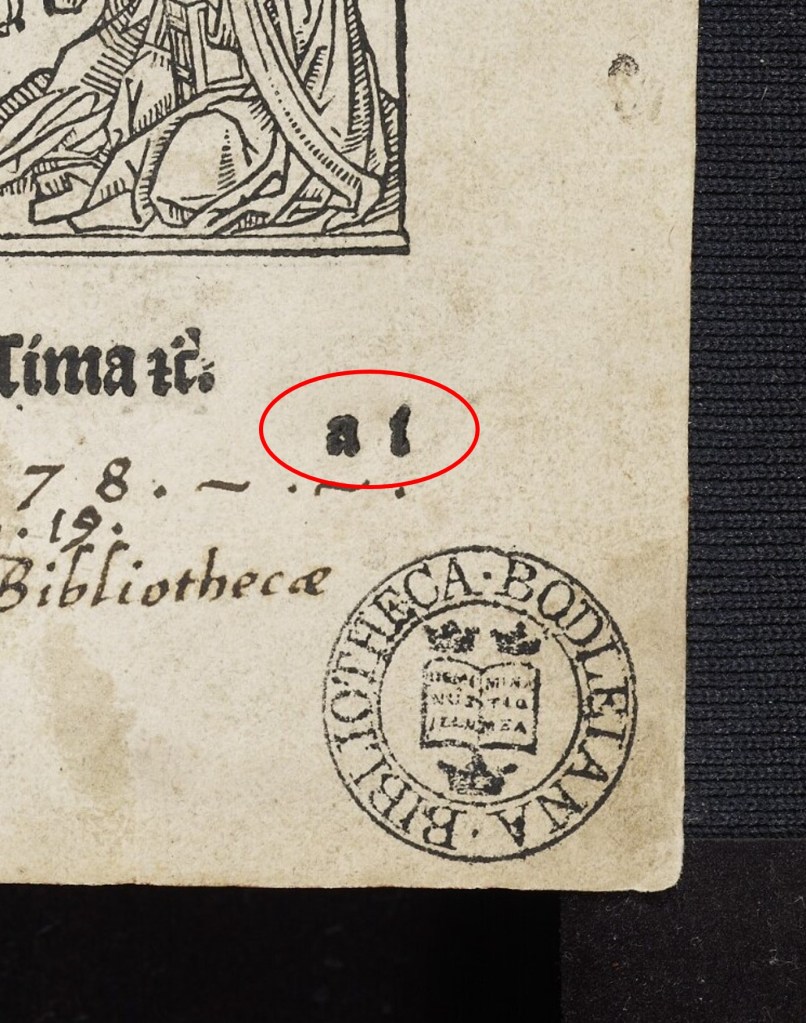

The process of collation begins with the first surviving leaf of the textblock. In our case, this is the title page, which I introduced above with reference to the woodcut illustration. Now, however, our focus is the printed signature in the lower right-hand corner, which says ‘a i’:

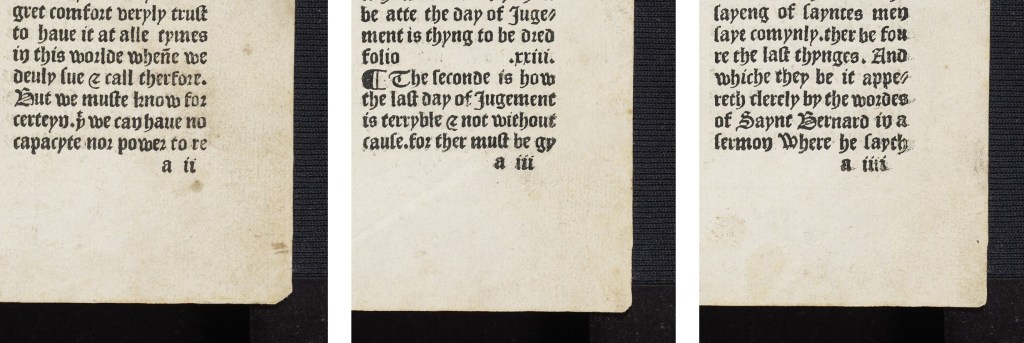

The ‘i’ here is a roman numeral, indicating that our leaf is the first in gathering ‘a’. On the next three rectos, in the same location, we find corresponding signatures for ‘a ii’, ‘a iii’, and ‘a iiii’.

Note that the number ‘iiii’ here is a variant for ‘iv’, which may be more familiar to you as the roman numeral for 4. In modern descriptions, you will commonly see signature references converted to Arabic numerals (i.e. a1, a2, a3, a4).

Returning to the book, we then find four rectos without a signature in the bottom right-hand corner:

These are the 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th leaves of gathering ‘a’.Each is physically connected to (and is said to be ‘conjugate with’) a leaf in the first half of the gathering, as explained in this diagram:

It was quite common to omit printed signatures in the second half of the gathering. This makes sense once you think about the practicalities of putting these four bifolia in the right order: if a1, a2, a3, and a4 are in the correct order, then a5, a6, a7 and a8 will necessarily be in the right place. Even when some leaves in a gathering are not signed (like our final four leaves here in gathering ‘a’), they are nonetheless referred to by bibliographers by their corresponding inferred signatures (in this case, sig. a5, a6 etc).

Beginning the collation formula

We have established, then, that our quarto starts with a gathering of 8 leaves. However, to keep physical descriptions clear and succinct, collations are normally described not with words and sentences but with collation formulae. These are sequences of letters and numbers that summarize the physical construction of the book in a universally understandable way. In our case, the first gathering would typically be described as a8.

It is important to emphasize here that a8 and a8 mean two different things. In collation formulae, superscript is often used to refer to the gathering structure, whereas unformatted numbers refer to the individual leaves. Thus, a8 indicates that gathering ‘a’ contains 8 leaves, whereas sig. a8 refers to eighth leaf in gathering ‘a’. Alternatively, subscript is sometimes used when referring to a specific leaf, for example in Bod-Inc (i.e. a8 in Bod-Inc means the same thing as a8).

Following the alphabet

The next gathering in our book is identified by the letter ‘b’, making it immediately obvious that it belongs directly after gathering ‘a’. Just like gathering ‘a’, gathering ‘b’ has 8 leaves, with printed signatures in the first half only. As before, these appear in the lower right-hand corner of the rectos:

The next eight gatherings continue to follow the same pattern, moving progressively through the alphabet to demarcate each new group of eight leaves. If you move through the digitization, you may notice that the sequence seems to ‘jump’ directly from ‘i’ to ‘k’. This is, in fact, entirely normal; early printed signatures generally use the 23-letter Latin alphabet (i.e. A‐Z less I or J, U or V, and W).

When collations follow this predictable structure, there is no need to list the gatherings individually in your collation, i.e. a8 b8 c8 d8 e8 f8 g8 h8 i8 k8. Instead, you can simplify this as a-k8. In a very concise way, this indicates to the reader that the first 10 gatherings are signed alphabetically, and each has 8 leaves.

A change in structure

Unsurprisingly, the next gathering in the book is demarcated ‘l’, following on from ‘k’. At this point, you might expect another gathering of 8 leaves, but in fact something slightly different happens. This shows the importance of paying close attention to detail when collating.

The gathering starts as we have come to expect, i.e. with l1, l2, l3, and l4:

However, there are only two more leaves in the gathering, where we might have expected to find 4:

What is happening here? Is this standard for our edition, or is this copy missing some leaves? In other words, is this a complete gathering of 6, or a gathering of 8 that is lacking two leaves in the second half?

You could, of course, answer this question by simply looking at the various bibliographical sources mentioned above. Bod-Inc, for example, will tell you both the collation of the ‘ideal copy’ (i.e. the presumed archetype), and whether the Bodleian copy deviates from it in any way. For the sake of this exercise, however, let’s focus on the internal clues that we can discern in the digitization.

Elements of continuity

The first thing to notice is that the edition includes printed leaf numbers or ‘foliation’ (note: the word ‘folio’ can be used not only to describe a book format, but also as a synonym for ‘leaf’). Almost every recto from sig. a4r onwards has a roman numeral in the upper right-hand corner, spanning from ‘i’ to ‘lxxxviii’, i.e. 1-88 (the first three leaves are unfoliated, as is the final leaf). For example, l4 is folio lxxxi [i.e. 81].

Foliation and pagination in early printed books are not always reliable guides, as often you will find repetition or omission of numbers. Nonetheless, the fact that there is no gap in the foliation sequence across gatherings ‘l’ and ‘m’ is conspicuous, suggesting that gathering ‘l’ is not defective but should indeed have 6 leaves only.

Tellingly, there is also no gap anywhere in the text at this stage. For example, the last verso of gathering ‘l’ ends mid-word (‘grevous’, meaning ‘oppressive’). The word continues at the first recto of gathering ‘m’. This further supports the impression that gathering ‘l’ truly is a gathering of 6, rather than an incomplete gathering of 8. The final gathering, ‘m’, likewise has only 6 leaves, and no obvious gap in content.

Stitching Clues

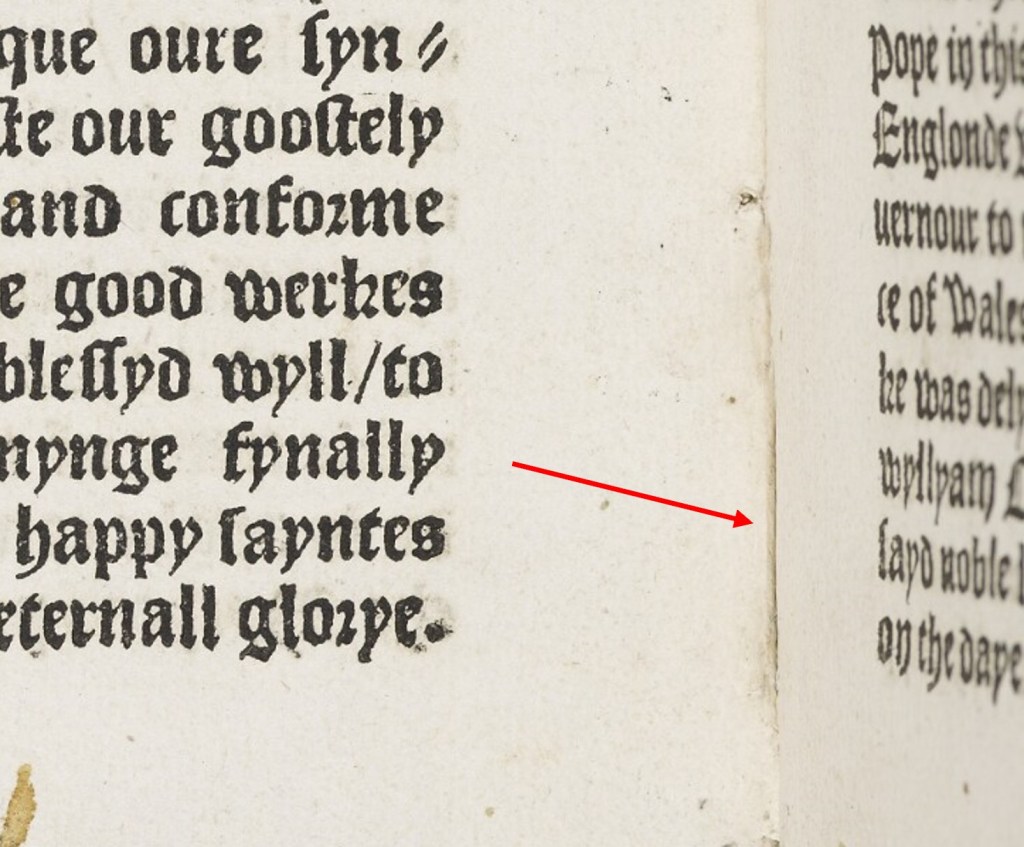

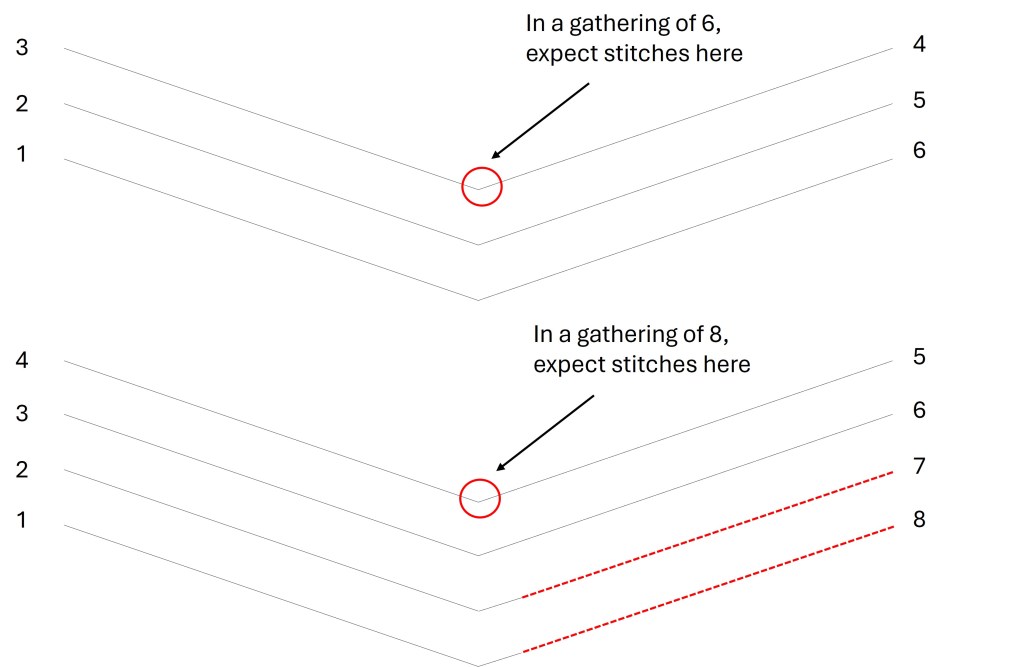

Something else to bear in mind is that stitches are usually visible at the centre of each gathering. This is important because the centre of a gathering of 6 and the centre of a gathering of 8 are in different locations, as reflected in the diagram below. If you suspect that two leaves are missing from a gathering of 8 (as represented here by the red dotted lines), the location of the stitching could help corroborate this theory.

Like watermarks and chainlines, stitches are generally easiest to see with the book in hand. Fortunately, in our digitization, you can see stitching between m3v and m4r—exactly where we would expect to find it in a gathering of 6:

Also conspicuous is what we do not see anywhere in gathering ‘l’ or ‘m’, and that is stubs. These narrow strips of paper are often visible in the gutter when leaves have been cut out or otherwise lost (we will see an example in part 4 of this blog post series).

With all of this in mind, we can infer that the book switches from gatherings of 8 to gatherings of 6 for ‘l’ and ‘m’. We can represent this in our collation as follows: a-k8 l m6. As ‘l’ and ‘m’ are consecutive letters, you don’t strictly need a dash to indicate range; you may also sometimes see this represented without a space, i.e. lm6, as in GW.

Reaching the end

There are clear signs in gathering ‘m’ that we are now at the end of the textblock. For example, the final leaf has woodcut illustrations on the recto and verso, both of which appeared earlier in the book. These were almost certainly repeated here to help fill out the blank space at the end of the text (a similar motivation likely explains the shift from gatherings of 8s to gatherings of 6; continuing in the former vein would have left 10 pages to fill at the end of the text, rather than just 2).

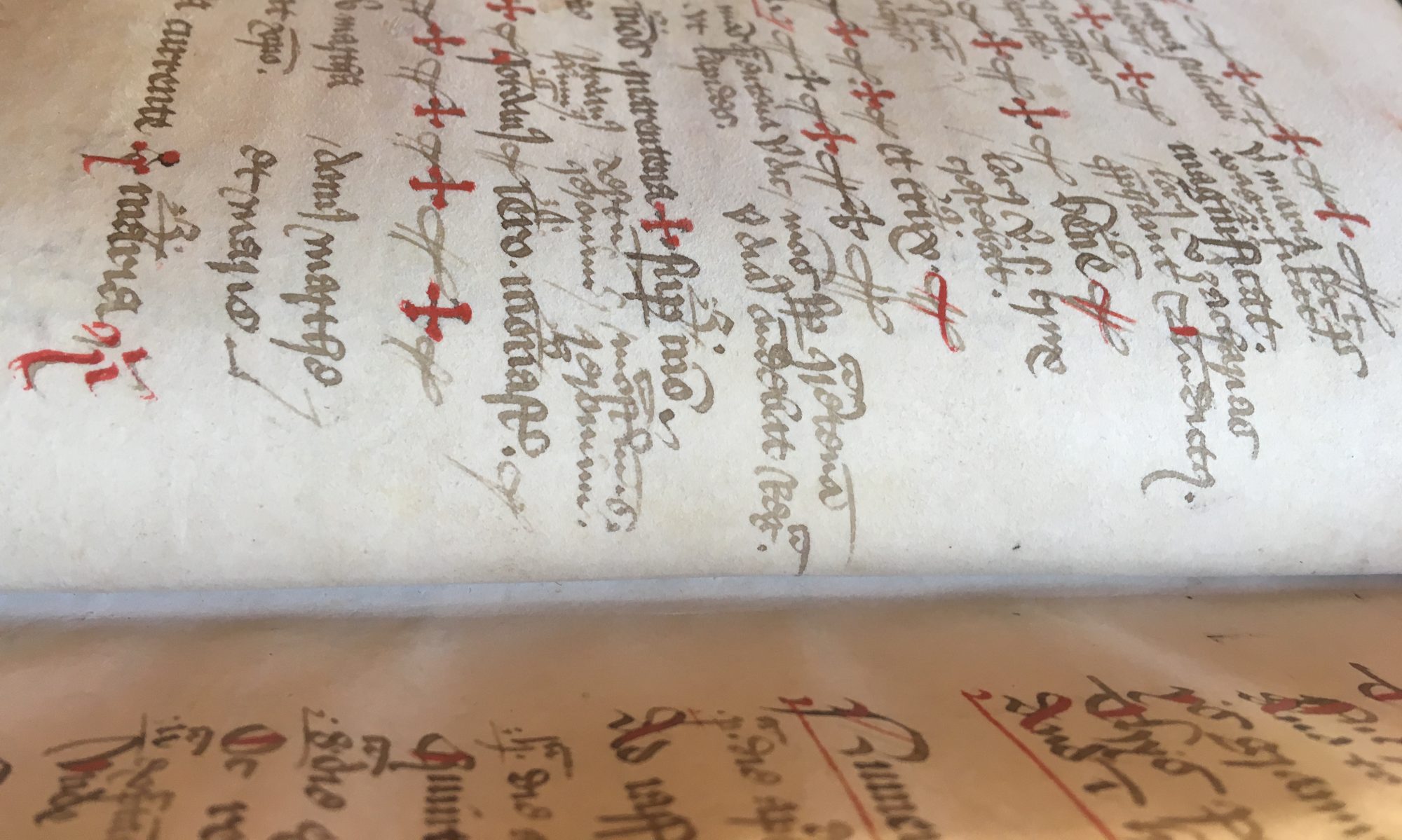

More importantly still, on the verso of the penultimate leaf, we have a comment about the particulars of the book’s production: ‘Enprynted atte Westmystre [i.e. Westminster]’:

Known as a colophon, these kinds of closing notes typically contain some or all of the following information: the imprint location (as here), the imprint date, and the name of printer. As is often the case, the colophon is accompanied in our book by a printer’s device, akin to an early type of logo. De Worde reused William Caxton’s distinctive ‘W C’ monogrammed device, a phenomenon I have discussed previously in a separate blog post.

In between the colophon and the printer’s device, there is information about the physical construction of this edition, usually referred to as the ‘Register’. Note especially ‘Registru[m] quatern[orum]’ (i.e. this is in quarto format), and a list of the letters assigned to each of the twelve gatherings.[1]

Though not always included in incunables, such information originally would have been of most practical use to the bookbinder. For us, it helpfully reinforces our impression that we are not missing any gatherings; the book should indeed end at ‘m’.

Internally, then, all our evidence points to this book being complete, with a collation of a-k8 l m6. This on its own, however, is not definitive. If you examine only one copy, ‘collation in this sense can do no more than reveal obvious imperfections’.[2] To strengthen our case that the book is complete, the next step is to compare our collation to another copy, or to consult a bibliographical description informed by multiple copies. We can achieve the latter by consulting Bod-Inc.

Checking Bod-Inc

The editorial convention of Bod-Inc is to list the collation formula for the ‘ideal copy’ under the imprint details. This is exactly the information we need: the bibliographical consensus on the typical collation for this edition, informed by comparison of multiple copies where available.[3]

Bod-Inc is additionally useful to us because it will allow us to check our collation of this specific copy. If the Bodleian copy deviates from the standard collation in any way, this will be specified under the COPY heading (e.g. ‘wanting a1’). If there are no comments on collation in the copy notes, then the copy is implicitly complete or ‘perfect’.

The latter is exactly what we find for our edition, described at C-458. The ideal collation is listed as a-k8 l m6, and there are no comments about losses etc in the Bodleian copy. Note also that the format is specified as a quarto (4o).

Our findings, then, are consistent with what is known about this edition (and this copy) more broadly: the Bodleian’s Cordyal is complete. Overall, this has been a relatively simple example, but we can now tackle some more complex cases in part 4.

[1] I have expanded printed Latin abbreviations here using square brackets. For a guide to this topic, see especially Erin Blake, ‘A briefing on brevigraphs, those strange shapes in early printed texts’, Folger Shakespeare Library blog, 2021, accessible here.

[2] Nicolas Barker and Simran Thadani (eds.), John Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors, ninth edition (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2016), p. 78.

[3] According to the editorial conventions in Bod-Inc, the collations given are ‘in the main, based on GW and BMC’ (see volume 1, p. lxxxiii).

2 Replies to “3. Collating in Practice”