Dr Sian Witherden is a rare books and manuscripts specialist who has worked in both special collections libraries and the antiquarian book trade. This post explaining paper formats is the second in a four-part series on collation.

Setting the context

In part 1, we explored what collation is and introduced our main case study for this series: the Bodleian’s second edition of Earl Rivers’ Cordyal (c.1494). Before we move on to the practical matter of collating the book, however, let’s review some practical matters relating to early printed book production. By the end of part 2, you will understand how paper was folded to create early printed books, and what terms like ‘quarto’ and ‘octavo’ mean. I will also guide you through the process of identifying the format of the Cordyal (c.1494). This context will make it easier to understand how collation works.

Folding paper

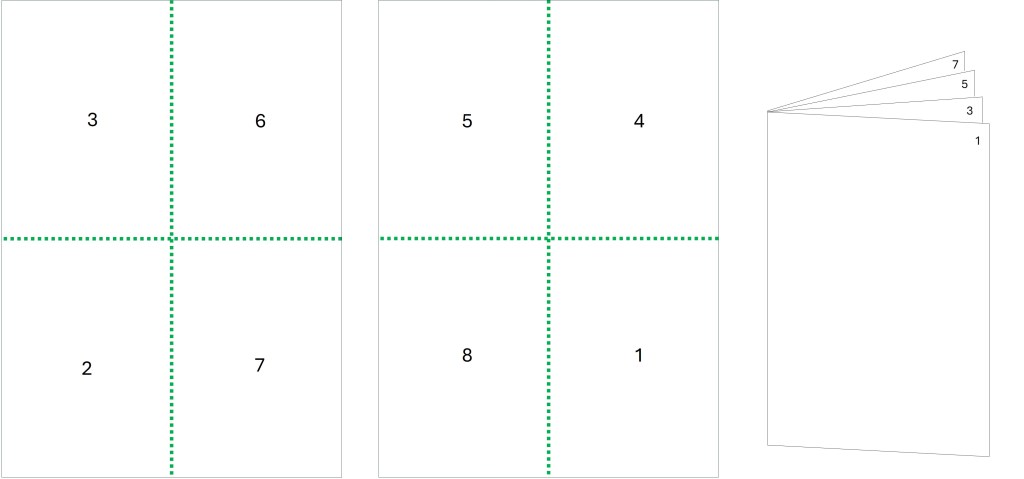

Most incunabula were printed on paper, though parchment (i.e. a surface made from animal skin) was sometimes used for this purpose.[1] The book production process typically involved taking large sheets of paper, printing them on both sides, and then folding as necessary. In the diagrams that follow, green dotted lines indicate fold lines.

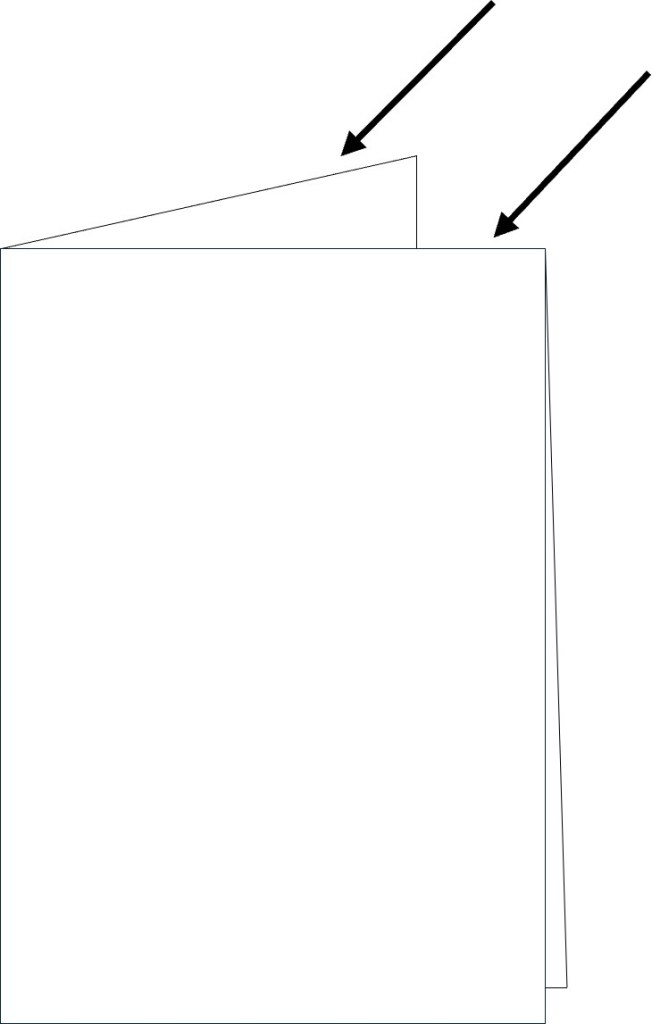

Folding a sheet in half produced a bifolium, i.e. four pages or two leaves (the front of a given leaf is known as the ‘recto’ or simply ‘r’, while the back is known as the ‘verso’ or ‘v’):

If the sheets were folded only once, then the book is said to be in folio format (often abbreviated to 2o). However, sheets could be folded yet further to create smaller formats. For example, folding a sheet twice creates eight pages, or four leaves. This is known as quarto format (4o or 4to).

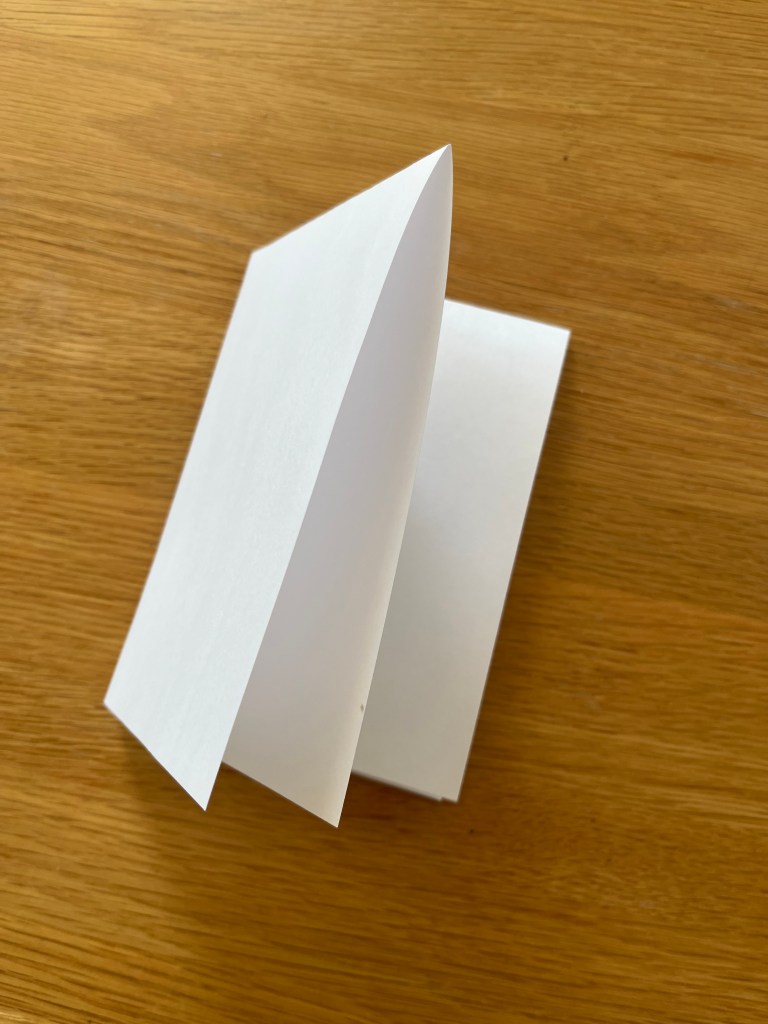

If you take a piece of modern printer paper and it fold twice like this, you will notice that it is not quite ready to use: the folds at the top prevent the leaves from being fully opened.

These folds are commonly known as the ‘bolts’, and in early printed books they needed to be sliced before use. Occasionally, you might encounter instances where this work was not completed, i.e. a book with ‘bolts unopened’ (a great example can be seen here).

Single sheets could be folded yet further to create even smaller formats, such as octavo (8o or 8vo) and duodecimo (12o or 12mo). Regardless of the format, folded units of paper (known as ‘gatherings’ or ‘quires’), would then be stacked and sewn together to form a longer entity known as the ‘textblock’. Gatherings often constituted a single sheet of paper, though not always; for example, you could nest multiple sheets together to create longer gatherings. Printed ‘signatures’, usually with a different letter for each gathering, helped to ensure everything would be bound in the correct order. As we will see in more detail below, this signature system informs how we collate early printed books.

Depending on the desired format of the book, the printed text had to be laid out differently on the sheets of paper so that the content would be in the right place once folded. These different layouts are known as ‘impositions’. For example, the diagram below shows how the two sides would be printed for quarto imposition (note: before folding, the text on pages 3, 4, 5, and 6 would be upside down relative to pages 1, 2, 7, and 8).

A great way to get a sense of how this worked in practice is to print out the Folger Shakespeare Library’s ‘DIY quarto’ and fold it yourself.

Determining Format

What is the format of the second edition of Earl Rivers’ Cordyal? You could, of course, establish this by consulting Bod-Inc or any number of other bibliographical resources (e.g. ISTC ic00907500, GW 7537). However, for the sake of this exercise, let’s work from internal clues.

Determining the format of an early printed book requires close attention to chainlines and watermarks. Both are a product of the specific way that paper was made in early modern Europe, as explored further in this Harvard Art Museums blog post.

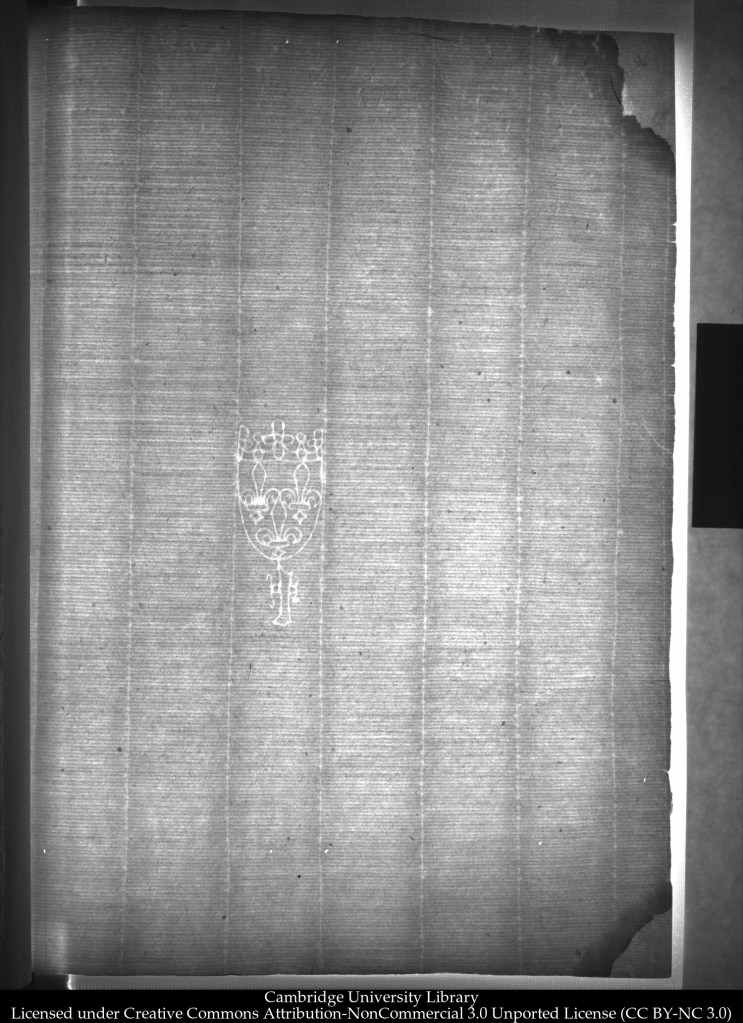

Chainlines and watermarks stand out best under raked lighting or with a light sheet underneath. Special photography techniques (e.g. mass spectrometry imaging) can also help to foreground chainlines and watermarks, as in the example below from Cambridge University Library. Note especially how the vertical chainlines and the watermark at the centre of the page are clearly visible.

Sometimes, chainlines and watermarks are faintly discernible in more conventional digitizations too. Crucially, the direction of the chainlines and the location of the watermark varies depending on how the paper has been folded. Looking for these features can therefore give you valuable clues as to format. Various references resources are available to guide you through this identification process.[2]

A closer look at the Cordyal

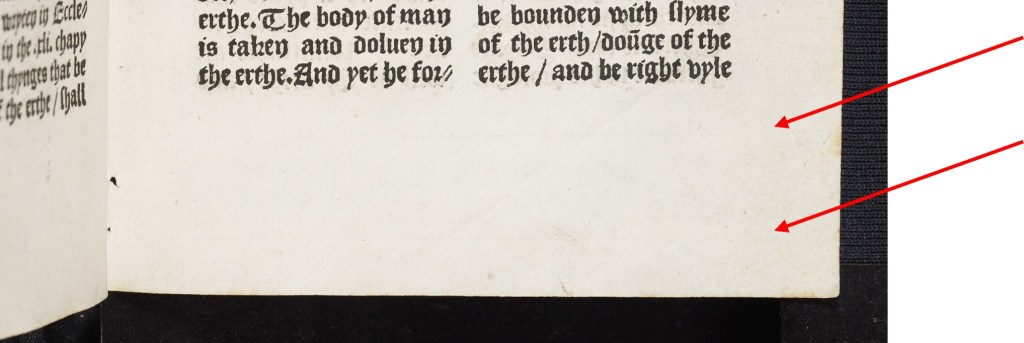

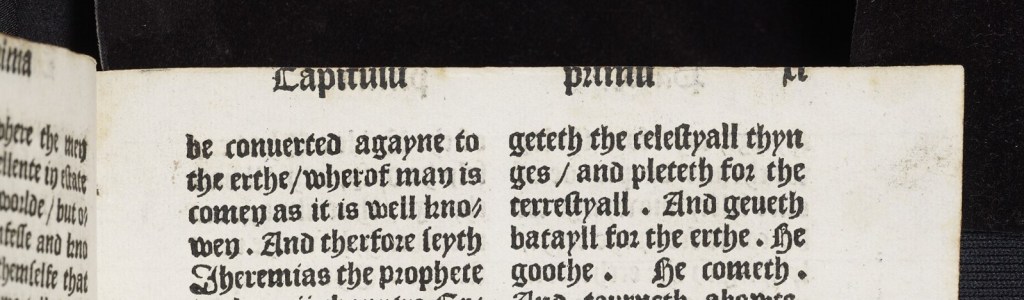

In the Bodleian digitization of the Cordyal, the chainline and watermark evidence is most clearly visible at sig. b6r (digitized here). If you look closely at the bottom of the leaf, you can faintly see two horizontal lines:

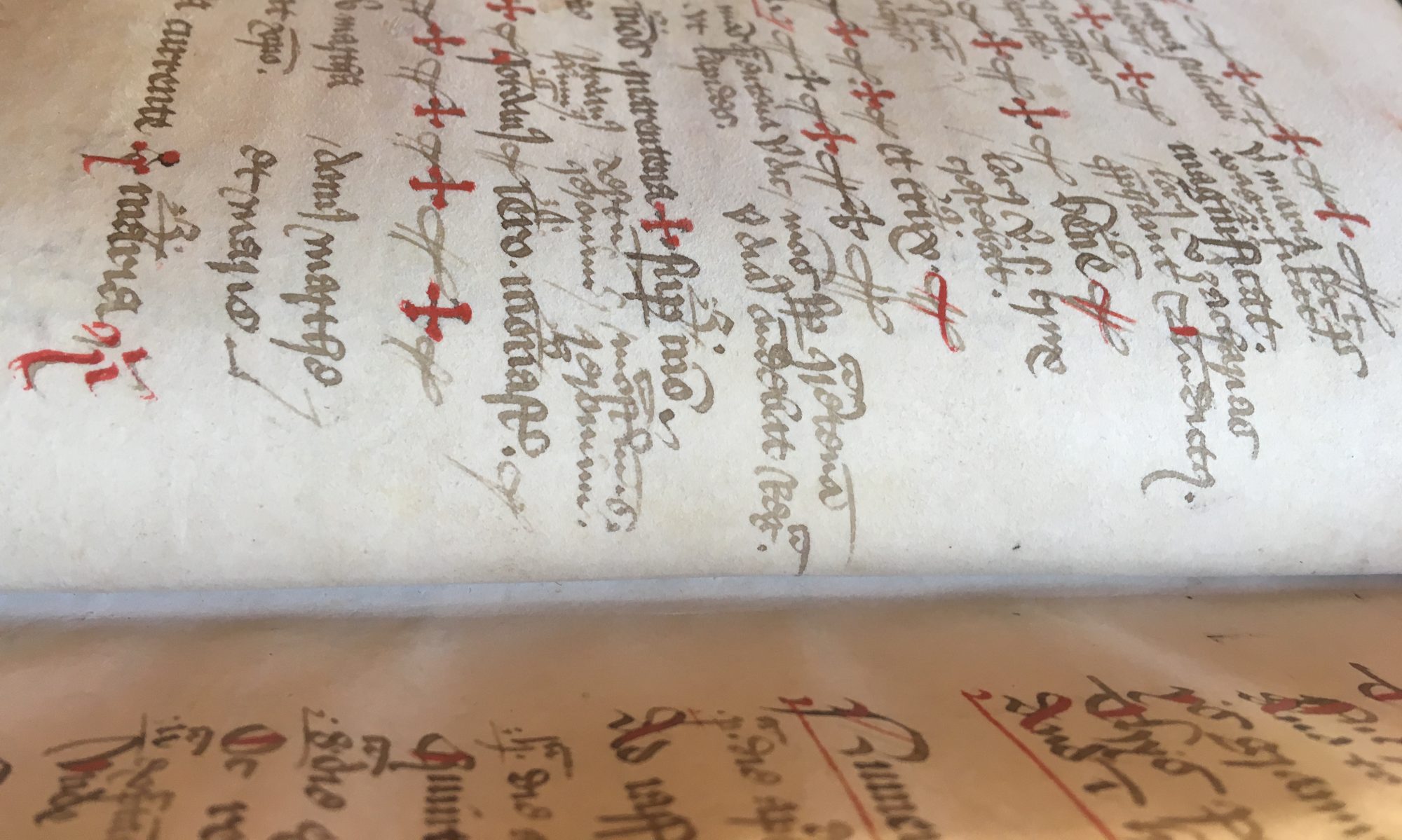

This is our first clue to the format. In folios and octavos, the chain lines run vertically. The presence of horizontal lines suggests we are more likely to be dealing with a quarto or a duodecimo. The location of the watermark is the next helpful indicator. In our case, part of the watermark is clearly visible in the spine fold or ‘gutter’:

This is fairly typical for quartos, though you will not find one on every single leaf.[3] For comparison, the watermark can appear in different places for duodecimos, including at the head of some leaves.

Although the overall size of the book is not a reliable indicator of format, it can be quite suggestive in combination with the chainlines and watermarks. Take note of the top of our page: it has clearly been trimmed down, with the result that the running titles are now partially shaved.

From this, we can infer that the leaves would originally have been slightly taller than their current height of 18cm. This again is broadly consistent with a quarto. Until the seventeenth century, quartos were often arranged in gatherings of 8, though other structures including gatherings of 6s can be found in incunables.[4] This will be useful to bear in mind in part 3 of the series, in which we will collate the book.

[1] See, for example, this book of hours.

[2] See especially Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography: The Classic Manual of Bibliography, repr. edn(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 79-117; Sarah Werner, Studying Early Printed Books, 1450-1800: A Practical Guide (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2019), pp. 46-53, and ‘The Needham Calculator 1.0’, accessible here.

[3] See further at (for example) Werner (2019) p. 48.

[4] For further details, see Gaskell (1995), p. 106.

2 Replies to “2. Identifying format”