Dr Sian Witherden is a rare books and manuscripts specialist who has worked in both special collections libraries and the antiquarian book trade. This post is the first in a series on how to collate early printed books.

What is collation?

If you are starting to learn about early printed books, you may well have come across something like this in a physical description:

a–k8 l m6

a–e8 f6 g–zA–I8 K6 L4

[a–i¹⁰ k l⁸ m–z A–H¹⁰ I K8 L–Z10 2a⁸]

All three of these are collation formulae, ranging from a relatively straightforward example to somewhat more complex ones.[1] These strings of text, which provide a succinct description of the physical structure of a book, can seem esoteric and intimidating to students first encountering them. Once you understand the basic bibliographical conventions behind collation formulae, however, they are relatively simple to decode.

Getting to grips with collation is a hurdle that is not unique to students of early printing. Medieval manuscripts are conventionally described in a very similar way, as Matthew Holford has explained for Teaching the Codex in ‘Reading a Manuscript Description’. My blog post likewise aims to demystify principles of bibliographical description, but with a focus on printed books rather than manuscripts.

In essence, collating an early printed book means to examine it — leaf by leaf — to determine how it was put together and to establish whether it is complete. A collation formula is the conventional way of recording the findings, allowing others to visualize and understand the structure even without the book in hand. It is perhaps easiest to explain how collation works by walking through practical examples, which I will do in this series using samples from the incunabula collection in the Bodleian Libraries. Incunables are books from the infancy of western printing, i.e. pre-1501 (the term is the anglicized form of the Latin ‘incunabula’, referring to swaddling clothes). While I concentrate here on the earliest stages of printing in Europe, the principles of bibliographical description covered are relevant more broadly for examining early printed books up to c.1800.

A case study for collation

Our main focus in this mini series will be an early edition of Earl Rivers’ Cordyal. Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers (d. 1483) was the brother-in-law of King Edward IV (d. 1483). For book historians, he is best remembered for his work as a translator and for his patronage of William Caxton, England’s first printer (d. 1491). Rivers’ Cordyal was a translation of Jean Miélot’s Quatre derreniéres choses, itself a translation of the Cordiale de quattuor novissimis ascribed to Gerard de Vliederhoven. The text belongs to the ars moriendi tradition, i.e. texts concerned with the art of dying well.[2]

The first edition of Earl Rivers’ Cordyal was printed by Caxton at his press in Westminster in 1479. Caxton’s successor, Wynkyn de Worde (d. 1534), printed the second edition that concerns us here. It is undated, but the most recent scholarship suggests that the probable imprint year was around 1494.[3] De Worde was still based in Westminster when he printed the Cordyal, though he would famously go on to become the first printer of Fleet Street.[4] The edition survives in just three copies (Bodleian Libraries, John Rylands Library, and Durham Cathedral Library).

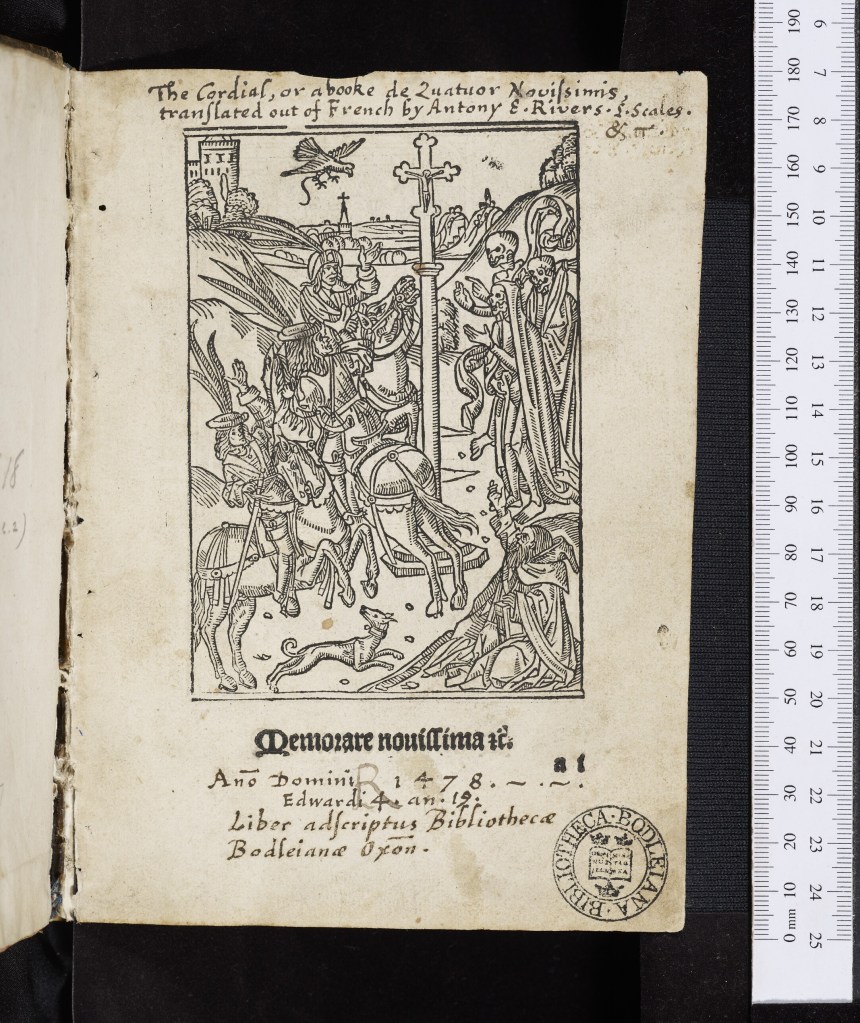

I chose this example for several reasons. The edition in general is relatively straightforward to collate, making it ideally suited for introductory purposes. The Bodleian copy has been fully digitized, which you may find useful to have open in a parallel tab while reading this blog post. Finally, this is a visually engaging incunable to work with, an added benefit for a task that involves going through every leaf! There are decorative woodcut initials throughout as well as four woodcut illustrations, one of which can be seen on the title page below:

This image depicts the Three Living and the Three Dead, a staple momento mori trope emphasizing the inevitability of confronting death. It was a common fixture of books in the ars moriendi tradition.

The Bodleian second edition of River’s Cordyal has previously been described and collated in a resource commonly abbreviated as ‘Bod-Inc’.[5] However, we will not look at the relevant entry quite yet, as it effectively gives the ‘answer’ to the task at hand. Incidentally, this makes resources like Bod-Inc an excellent tool for self-learning. To test your understanding of the topic you could pick an early printed book, have a go at collating it yourself, and then revert to an authoritative description to check your working.

Similar resources exist for some other major incunable collections, including ‘BMC’ for the British Library.[6] It is also good to be aware of ISTC (Incunabula Short Title Catalogue) and GW (Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke), two online union catalogues for incunables. These electronic databases record bibliographical data reflecting the combined holdings of multiple libraries, as opposed to the copy-specific information prioritized in resources like Bod-Inc and BMC. GW in particular is often a helpful place to check to establish what your book’s collation ‘should’ look like, i.e. the ‘ideal copy’. Both ISTC and GW are also excellent tools for locating online digitizations. Now that we have introduced our main case study, let’s have a closer look at paper format in part 2.

[1] Respectively, these collation formulae are quoted after Bod-Inc C-458, J-225, and G-178.

[2] On this text and tradition, see especially Omar Khalaf, ‘Memorae novissima: Caxton’s and de Worde’s editions of Earl Rivers’ Cordyal and the Macabre in a late medieval English Ars Moriendi’, in Alessandro Benucci, Marie-Dominique Leclerc, and Alain Robert (eds.), Mort suit l’homme pas à pas: représentations iconographiques, variations littéraires, diffusion des thèmes (Reims: ÉPURE, 2015), pp. 275-86.

[3] Lotte Hellinga, ‘Tradition and Renewal: Establishing the Chronology of Wynkyn de Worde’s Early Work’, in Kristian Jensen (ed.), Incunabula and Their Readers: Printing, Selling and Using Books in the Fifteenth Century (London: British Library, 2003), p. 28.

[4] James Moran, Wynkyn de Worde: Father of Fleet Street, 3rd rev edn (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2003).

[5] Alan Coates et al., A Catalogue of books printed in the fifteenth century now in the Bodleian Library,6 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[6] Catalogue of books printed in the XVth century now in the British Museum [British Library], 13 vols. (London, ’t Goy-Houten, 1963-2007).

2 Replies to “1. Introducing Collation”