Sebastian Dows-Miller is a doctoral student in Medieval and Modern Languages at the University of Oxford (St Hilda’s College). His research interests centre around the manuscript transmission of short texts, with a particular interest in those written in Old French. He is a lecturer at Hertford and Merton Colleges and a member of the Teaching the Codex committee. This is an edited version of his presentation at the Teaching the Codex workshop on Hybridity on 17th May 2024.

Most of us who teach medieval literature at an undergraduate level will probably, at some point or another, have encountered a sentence like this one:

The final line of the passage invites the audience to pay attention to what the characters have to say, with the author’s use of the exclamation mark building suspense…

Beyond simply reacting with great wailing and gnashing of teeth, what can we surmise from these sorts of claims about students’ understanding of medieval textual culture, and how ought that to inform our teaching practices?

Fundamentally, it is important to remember that such lack of understanding is not the students’ fault, but our own. How are they to know that medieval punctuation practices were vastly different from our own, if we don’t tell them, especially when they are encouraged to comment on punctuation by colleagues teaching more recent texts? Why wouldn’t they assume that the modern editions that they encounter aren’t fully faithful representations of some ‘original’ text?

The fundamental issue is that medieval vernacular literature is increasingly taught in an environment that is abstracted from the material contexts of these works.

To take an example, let’s consider the teaching of medieval French literature at Oxford, my home institution. The students’ first encounter with a medieval text comes in their first year, when they study La Chastelaine de Vergy, a 13th-century courtly poem of about 1000 lines. The exam is text-based, involving essays written with reference to critical editions of the texts (and a modern French translation). The teaching is therefore, quite sensibly, predominantly textual, focussing on the text of these critical editions, with limited introduction to questions of materiality.

While the approach to teaching the Chastelaine therefore makes sense from an exam perspective, it does still result in statements like the above, and means that the students miss out on an opportunity to engage with the richness and excitement that engagement with codices can provided.

So, what do we do about this?

I have two, not particularly groundbreaking, suggestions for how we can introduce materiality into textual teaching contexts:

- The first is simply that starting at the very beginning is a very good place to start. If we bring in materiality before students even encounter their first medieval text, then misconceptions about medieval texts are less likely to become ingrained.

- Secondly, we must reinforce and build on these initial encounters, by incorporating materiality into all teaching contexts.

To achieve this, before we even start to think about the Chastelaine, I run a session introducing the students to manuscripts and early print books from the collection at Merton College, brilliantly facilitated by the library team and in particular Julia Walworth, the Fellow Librarian, to whom I’m hugely grateful.

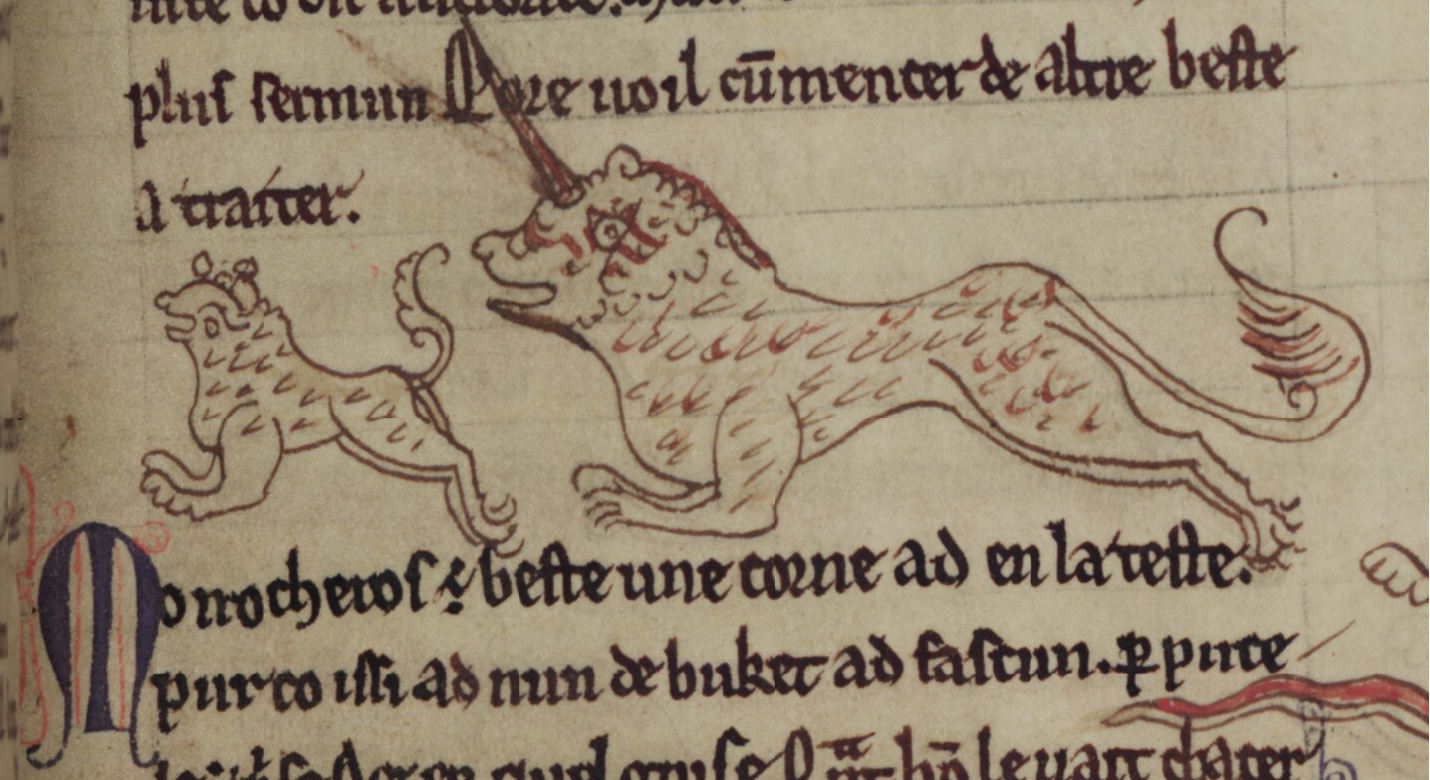

I take the students out of their comfort zone by focussing on an object the likes of which they have probably never encountered: MS 249, which contains a 13th-century bestiary in Anglo-Norman French. The text type is therefore totally unknown to the students, and the language is unfamiliar, but not totally impossible for them to understand.

However, we don’t start by looking at the text, as students of literature are so keen to do. Instead, we think about the materiality of the codex: its binding, the use of parchment as a writing support, the evidence of a historic chain staple and the value that this indicates. In short, my intended takeaway is for the students to realise that the medieval book is not the same as a modern one, giving them a sense of distance and foreignness that helps break down existing preconceptions, and creating a more assured basis for understanding.

Then and only then do we turn to the text. I introduce them to various of the bestiary’s examples, along with its illustrations, generating interest and pushing the boundaries of the students’ knowledge, without expecting them to do anything new.

Then, I once again take the students outside of their comfort zone with some basic palaeography. We look at the section below, and I ask a student to volunteer to read the first two lines. They can usually get the first word, ‘Monocheros’, and through a bit of basic etymology they’re able to identify that this refers to a unicorn.

Then they get stuck. They encounter an unknown symbol that is clearly not one used in the modern writing system, besides some resemblance to the division symbol. This gives me the opportunity to explain the use of abbreviation in medieval codices, as an example of significant difference between the modern and medieval writing systems, thereby increasing the sense of distance between the two contexts.

Having identified that this symbol is an abbreviation for ‘est’, we come to the conclusion that the first line reads: ‘Monocheros est beste une corne ad en la teste.’ which given the similarities with Modern French the students can translate to:

The unicorn is a beast. It has a horn on its head.

We then get our first instance of medieval punctuation! Again, this comes as an example of the difference between modern and medieval systems: here, the punctus at the end of a line is used to indicate the end of a rhyming couplet, and none of the punctuation appears between the two lines, as we’d expect in the modern system.

We get a similar story on the next line:

pur co issi ad nun de buket ad fascun.

[That’s how it gets its name. It looks like a billy goat.]

Here, through forms like ‘pur’, ‘co’, ‘nun’, and ‘ad’, I’m also able to give the students a better understanding of medieval orthographic variation.

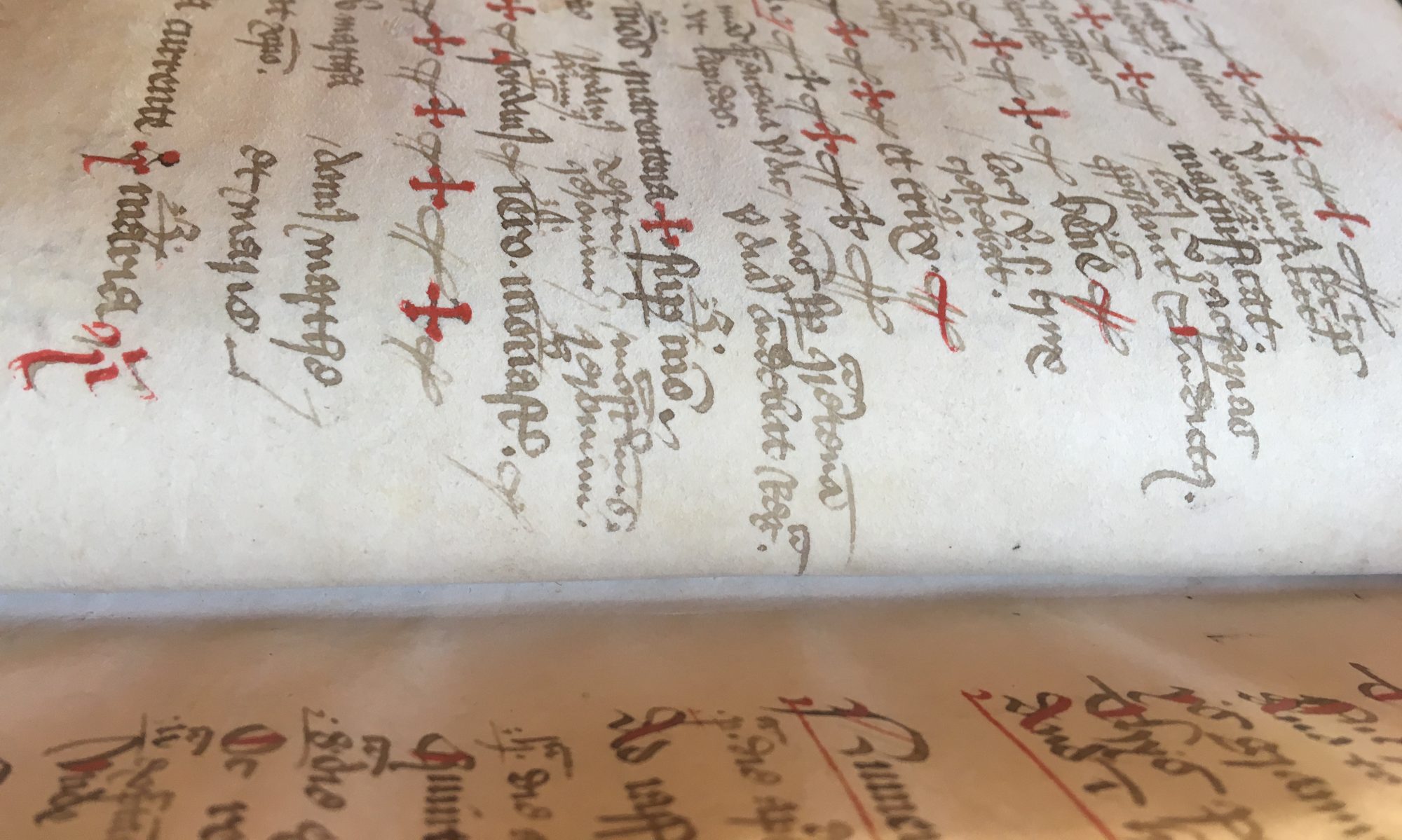

To compound this point, we look at the versions of this section of text that has been presented in critical editions. I use older editions because these tend to provide more evidence of departure from the manuscript, in this case the editions by Wright (1841) and Walberg (1900), given below:

MS Transcription:

Monocheros est beste une corne ad en la teste.

Pur co issi ad nun de buket ad fascun.

Critical Editions:

Monocheros est beste,

Un corne ad en la teste,

Pur çeo ad si a nun,

De buc ad façun.

Wright, 1841

Monosceros est beste,

Un cor at en la teste,

Pur ço issi at num,

De buket at façun.

Walberg, 1900

By comparing the manuscript transcription to the critical editions, the students are able to identify a few key differences. First, the fact that poetry could ever be presented in concatenated lines proves a revelation for many, as well as having an impact on our understanding of how the text was read.

Again, we get an example of the differences between modern and medieval punctuation and orthographic practices, as well as the revelatory fact that critical editions don’t rely on just one manuscript, and can include editorial ‘corrections’, such that the text encountered within doesn’t necessarily bear full resemblance to a medieval reality.

In our next session after the library visit, when we start to encounter La Chastelaine de Vergy for the first time, we start by critically examining our physical editions, and comparing them to the manuscripts that we saw. We think about how the manuscript context affects our reading of the text itself, particularly in what it means to talk about authors and readers, as well as the benefits and dangers of focussing on single words. The conclusions that I want the students to draw are straightforwardly those of caution and common sense: I want them to be wary of making claims about the text that are tied to some material feature of the modern edition, while also applying their common sense to identify points that fit with the manuscript contexts that they have seen.

So, how does this turn out for the students? I find that this approach has a double impact: it usefully increases the students’ understanding of the text that they’re studying, while also having the possibility of creating a few baby medievalists along the way. By pushing the boundaries of their knowledge in material matters, their ability to engage with medieval texts develops far more than it would have in a solely text-based session.

And, most importantly, nobody mentions the punctuation.

Sebastian Dows-Miller, St Hilda’s College, Oxford

One Reply to “”